In the wake of Jürgen Moltmann’s passing, I wanted to share my own thoughts, a livestream with Philip Clayton, previous podcast episode, and a list of other reflections on his life and legacy. Scroll down to access everything.

“If you live a while, you will finally ask a scary enough question to become a real theologian.”

That’s what a benedictine monk said to me once at the end of a week together. He said it like a koan, smirked, and then finished saying his goodbyes to the others who joined the retreat. We had talked about God and life all week, so I wasn’t exactly sure what he meant. It wasn’t until life stomped all over my soul that I figured it out. Until then, I had no idea what he meant, and it honestly irritated me.

Why would it take going through my own personal hell to become a real theologian?

What is gained from going through a period of darkness, anguish, and suffering that, at least theologically, you couldn’t learn from reading about it? Seriously, until I got there, I refused to believe all that was necessary to become a theologian. Now I not only think it’s necessary to have life beat a scary question out of you to be a theologian, but that Jesus also needed to ask one if God was ever going to understand and redeem the world.

Jürgen Moltmann was the theologian who helped me have the courage to ask if God really gives a shit. The 20th Century saw more human slaughter and suffering than anyone could have anticipated. The growth of democratic nation-states, the free market, and the Industrial Revolution did not bring a century of peace but rather one of war and unimaginable suffering. After the dropping of the atom bombs and the horror of Auschwitz, viable Christian theology became a problematic endeavor. At no other time in recorded history were humans more aware of just how vile we can be as a species. To talk about a loving and sovereign God seemed more and more laughable. If the church cannot address the actual world and its genuine horrors, then it should just shut up.

No theologian more directly faced the challenge that evil and suffering placed on theology than Jürgen Moltmann.

From a Scottish prisoner of war camp, this former German soldier began not only to pioneer a path forward theologically but did so in a specifically Christian way. For Moltmann, Christian theology had long ignored its very center — the cross. In his theology of the cross, Moltmann insisted that Jesus’ own experience of godforsakeness on the cross should ground theology. What this means and its dramatic impact on Christology will need to be developes clear t’s clear that Moltmann found himself a brother in Jesus when he cried out, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?”

In that statement, he heard Jesus dare to say to God the very words of protest demanded by humans throughout the centuries amid suffering. While he would go on to develop some amazing theology, it was the simple yet powerful recognition that Jesus knew and shared the ugliest and worst of our experiences that gave him a brother.

The first time I read Moltmann with a group of students, one of them summarized him by saying, “In Christ, God not only gave a shit, but got in our shit to make beauty out of it.”

For most of the Church’s history, the experience of Jesus on the cross was more or less dismissed.

The image of divine perfection, inherited philosophically from its Hellenistic dialogue partners, couldn’t manage a God who knows suffering internally. The suffering was primarily seen as a necessary part of God’s atoning work, but not as an event within the divine life. To preserve the perfection of God, it was theologically problematic to say that God could experience the suffering of Jesus. Divine perfection required that God was impassable and immutable, which meant that God could not change nor share in suffering, loss and pain. If God were imagined to have somehow changed in light of a creature’s decision or burden, then God would have changed, either for the better or worse, thus revealing that God’s previous state of being wasn’t as good as it could have been. Here’s the thing: this notion of divine perfection is not based on the God revealed in scripture, nor is it logically connected to what we know about Jesus. To preserve this non-Biblical notion of divine perfection, the historical church has had to quarantine the pathos of God in the Hebrew scriptures theologically and the experience of Jesus from God’s essence.

The pathos of God, a concept Jewish theologian Abraham Heschel first drew Moltmann’s attention to, is the overwhelming commitment of God to the people of Israel. Within God, there is a vulnerability and investment in God’s own people that makes the historical process matter within God and to God. In the Prophets, for example, we come to see a God who cares about the plight of the poor and oppressed — a God who is set against the godlessness of the world. God’s passion is displayed in compassion for others, one that shares in their sufferings and rejoices in the joys of others. This Biblical pathos of Israel’s God was made flesh in the person of Jesus.

For Moltmann, an impassible God is not really a God, but a demon!

God is the one who cares. The strength of this assertion comes not from Moltmann’s own experience but from the cross of Christ. When theologians have traditionally asked, “What suffers on the cross of Jesus?”, the answer is based on the two-natures of Jesus’ person: his full humanity and divinity. The usual response would highlight that the experience of suffering and godforsakenness was limited to the humanity of Jesus, but was incompatible with his divinity. In stark contrast, inspired by the pathos of God, Moltmann locates the cross of Jesus in the very heart of God.

The cross of Jesus rightly understood must be a Trinitarian event. In fact, for Moltmann, the entire logic of the Trinity and the meaning of Christian theology must be worked out from the cross. The problem with traditional trinitarian thought is that it sought to palatably incorporate the humiliation and rejection of Jesus on the cross into the Trinity. The order must be reversed. When Christians speak of God, we must not mean a generic concept of an infinite deity. The word “God” is defined by God in Christ who was crucified and raised. This not only means that God suffers with Jesus, but that the divine life is changed, the pathos of God is embodied, and the eschatological shape of the divine life is revealed — meaning the crucified but risen one reveals God’s presence in history, participation in our suffering and promise for new life.

On the cross, the Son experiences and dies abandoned by the one he called Abba. But in his rejection, suffering, abandonment, and execution, the Son is not alone, for he has become the brother of all the abandoned. This brother of the forsaken is also the eternal Son who, in his identification with them, also brings the presence of God. For Moltmann, only the crucified God can be the good God of the crucified people. God’s relationship to the cross is not through the Son alone but all three persons. The Father is moved to intense grief by this event, as the one who can truly know the death of the Son. The Spirit preserves and gives new life and hope to this relationship on the other side of death.

For Moltmann, this signals that the triune God is not the God of heaven who resides elsewhere. On the cross of Jesus, God has identified with the guilty and the forsaken, overcoming their alienation from God, and bringing them the promise of their own future in the divine life. The Triune God is the God of history, whose pathos for the world not only experiences the death and resurrection of Jesus, but promises to do the same for all.

In one of my favorite passages, Moltmann puts it this way, “All human history, however much it may be determined by guilt and death, is taken up into this ‘history of God’, i.e. into the Trinity, and integrated into the future of the ‘history of God’. There is no suffering which in this history of God is not God’s suffering; no death which has not been God’s death in the history of Golgotha. Therefore there is no life, no fortune and no joy which have not been integrated by his history into eternal life, the eternal joy of God.”

The image of God and God’s relationship to history must be redefined, according to Moltmann. Just as the future of the cross-dead Christ was in God and not death itself, so too is the future of the world in God. This is not an image of hunky-dory universalism that ignores the reality of history and the tragedy of our world — No! God has embraced, shared, and is reconciling all the violence of history. It’s not being denied nor neglected, but embraced. Because the Son was excluded, all the excluded will now be included in God’s reconciling work. What blew my mind the first time I read Moltmann was this — that Jesus Christ is the human face of God, and without it Moltmann would reject God in general, because God would have rejected all those discarded throughout history’s bloody trek. It is only through the message of the kin-dom, his suffering on the cross, and the promise of God through the resurrection, that he could imagine believing in a deity — let alone a God who is love. Said another way, history demands the death of God and stands as a valiant witness against God’s existence. Only the crucified God could justify speaking the name of God again.

I could say much more about Moltmann’s brilliance and how his ideas continue to shape my own. On Monday, I will share a two-hour conversation with Dr. Philip Clayton in which we do just that.

Some of this reflection was taken from my book The Homebrewed Christianity Guide to Jesus.

Celebrating the Life, Legacy, and Thought of Jürgen Moltmann

Philip Clayton was my PhD advisor and remains a mentor and friend. We scheduled a livestream session where we planned to explore contemporary options for the doctrine of God by developing a typology of live options, but when we learned of Moltmann’s passing, it seemed fitting to pivot our plan and reflect on the life, thought, and impact of Moltmann for Christian Theology.

Watch the video or listen to the podcast (ad-free member feed)!

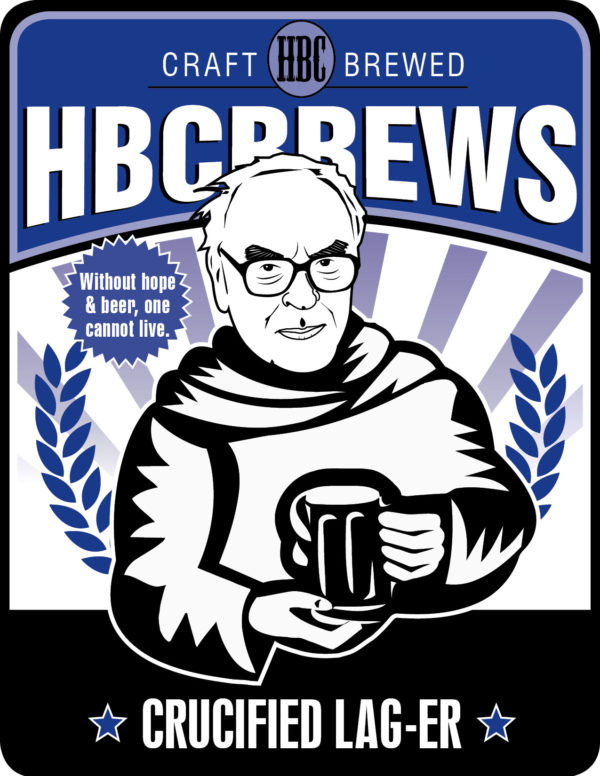

Moltmann’s Beer

Over the years, I have created unique beers for a select group of theologians and unveiled them at live Homebrewed Podcasts. This is the label for Moltmann’s beer. We christened it with him at the live podcast. We ended up signing books together at the Fortress booth that AAR. He had a line of scholars bringing their well-worn copies of The Crucified God up to be signed, and I was signing my first book, Homebrewed Christianity Guide to Jesus: Lord, Liar, Lunatic, or Just Freaking Awesome.

There was less of a line for me and more of a circle of the grad students who listened to the podcast. Afterward, Moltmann signed my copy of his book and said he had read the chapter in my book about him and was surprised at how well I captured the energy of his Christology in a compelling way. Then he took a deep breath and said, “Too many American theologians of your generation avoid writing a Christology or addressing the horror of history. May you never leave either behind. That is the Christian task of theology.” I was dumbfounded like Luke after Yoda drops a wisdom bomb on him. In preparing all my notes for the live stream with Philip, I went through my class lectures and notes in his books, and I felt the energy of Moltmann moving in my imagination anew. Hopefully, some of it came out in our conversation.

Homebrewed Interview with Moltmann from 2022

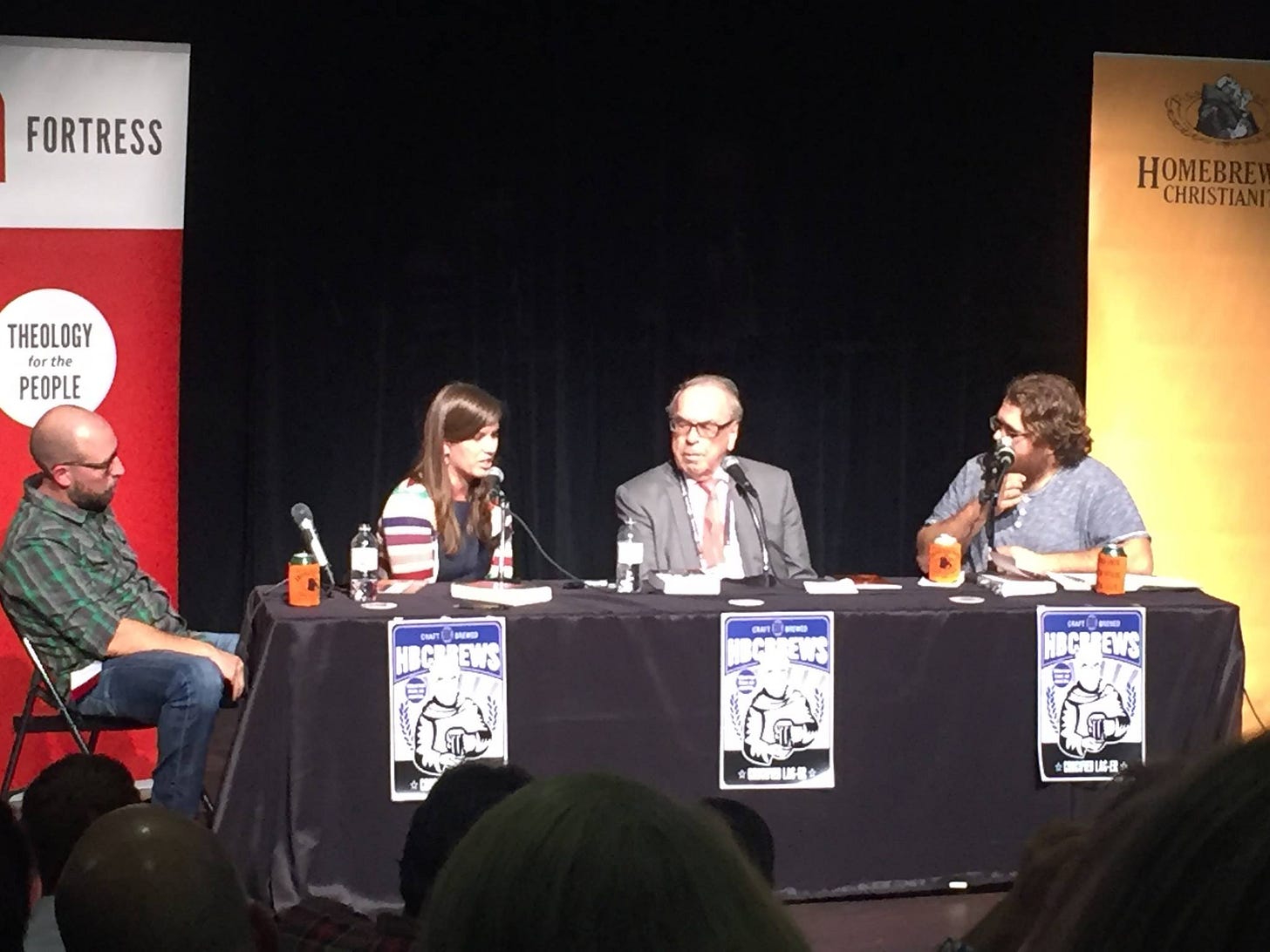

This is the first half of the live HBC podcast from the American Academy of Religion in 2022. You will get to hear Tony Jones and I interview the zesty German one – Moltmann! During the podcast, we celebrate the 40th anniversary of Moltmann’s ground-breaking text The Crucified God. We were also joined by Jennifer McBride and Philip Clayton.

Podcasts About Moltmann’s Legacy

Remembering Moltmann with Rolf Jacobson and Ruben Rosario Rodriguez

Theologian of Hope: Remembering Jürgen Moltmann (1926 – 2024) with Mirslov Volf

All the audio of Moltmann from the Emergent Village Theological Conversation with him

Written Reflections on Moltmann’s Legacy

Former student Miroslav Volf’s beautiful reflection, Yale University

The great attraction of his theology is that it is “fresh,” close to the pulse of life. He wrote about things that move people—about suffering and joy, about exploitation, discrimination and solidarity, about the travails of God’s creatures under human greed, about life and death. And he wrote about life by exploring the great themes of Christian faith: God, Christ, Spirit, creation, redemption, and new creation.

Former student Michael Welker in Theology Today, reflecting on the heartbeat of Moltmann’s thought…

Those who hope in Christ can no longer resign themselves to the given reality, but begin to suffer from it, to contradict it. Peace with God means discord with the world, because the sting of the promised future is relentlessly digging into the flesh of every unfulfilled present.

“The Fullness of Life” from the University of Chicago, Janna Gonwa

Church Times, Dr. Natalie K. Watson

Insights from the Uniting Church Australia

Once upon a time when I signed up to support HBC I was in part lured by the prospect of a promised theology course that I needed to understand the Reformed world and how to understand it with a hermeneutic of charity and relate to it as a branch of family and embrace it as fellow travelling co-workers in the vineyard. Coming to reflective consciousness in the wake of Vatican II, I was taken by the mixed signals, the documents and new practices which established new norms for community and experience, passed along by a bureaucracy gone ricketty and seemingly unresponsive to the challenges of a new time, still chewing up the innocent under the guise of "la bella figura", the public face of Holy Mother Church, managed and coiffed by the old Constantinian playbook. Good Pope St. John tried to throw open the windows and allow the Spirit to blow through, but in his wake the reactionary forces of cassock-wearing Latin lovers followed behind, trying to pull 'em back down shut, lest what was inside be lost to the outside.

I kept wondering when the course would show up. Having gone to grad school I eventually became reaccustomed to the formula of the seminar-length podcast. I came to know about people like St. Howard Thurman and St. Phyllis Tickle (we all need to reappropriate the ancient practice of popular acclaimation of our heroes) and started to get a better sense of the lay of the land.

With this essay on Moltmann, I consider the course to be fully delivered. I'm getting my copy of The Crucified God today. This Boomer is biased towards long-form and Substack is a healthier, friendlier venue than the toxic Superfund sites that Facebook and TwitterX have devolved into. Somehow Substack seems to fly under Mammon's radar, for now at least. This is only a confession of personal prejudice so please continue to be alert for the signs of the times and watch for new developments, after all who am I to judge?

Rock on witcha bad self. Gotta keep an eye on those Benedictines - they're a sneaky fifth column in a Canticle for Leibowitz kind of way. And what an amazing gift from Herr Prof. Moltmann.

It's good for us to be here. Good place to put up a tent or tabernacle or something. Peace and every good!

Don from Nashville

Tripp, I'm delighted you have moved to Substack, and love this brief summary of your thoughts on Moltmann. I don't always have time to get to all your podcasts, so this is helpful. Thanks for taking the time to do your work of bringing theology to busy pastors at a time when seminaries are closing.