When Christians try to answer the question “Who is Jesus?” they are engaging in what theologians call Christology. True, it’s not nearly as cool a name as the doctrine of the Holy Spirit, pneumatology, or the End Times, eschatology, but what Christology lacks in a sweet-sounding label, it makes up for in sheer bravado. Christology is just plain crazy. It is ridiculous. Most any spiritual person could have a conversation about the Spirit, and half of the movies coming out of Hollywood are about some dystopian apocalyptic future, but when Christians start talking Christology, people get nervous. That’s because Jesus was a homeless, itinerant, first-century rabbi who talked about the end of the world, taught in parables even his disciples couldn’t follow, and ended up dying on a Roman cross as a failed political resistor. That is the Jesus we call the Christ, the Son of the living God, the First Born of all creation, the Image of the invisible God, the eternal Logos, and all of the other christological titles packed into the New Testament.

While the titles easily roll off our tongues in worship and are around every corner in the Bible, how to apply them is not immediately obvious. Personally, I love them, sing them, and proclaim them, but I think we would be doing ourselves and Jesus’ PR firm a favor if the church were a little more aware of how we sound to outsiders. For many who grew up in the church, even those who no longer attend regularly, identifying Jesus as the Son of God is completely reasonable. We may roll our eyes whenever the latest New Atheist prophet or biblical scholar gets on TV mouthing off all sorts of reasons to doubt these names and claims, but when Tom Cruise explains the veracity of L. Ron Hubbard’s science fiction we roll them for a different reason. It’s absurd.

Yes, that was a Scientology joke. But if you simply switch their religious myth with ours, you get the point. Christology is packed full of strong, absurd, and tenuous affirmations about Jesus. What we say about Jesus and even how we celebrate God’s work in him is shocking when looked at from the outside, and it always has been.

Pliny the Younger is not simply the name of Russian River’s legendary Triple IPA, available for two wonderful weeks in February. Pliny was also the governor of Pontus, province of Asia Minor, from 111 to 113 ce. One of the few times Jesus and the early church is mentioned by someone not part of a Christian community is in the correspondence between Pliny and the Roman emperor Trajan. Below is a wonderfully revealing piece describing how the first Christians sounded to outsiders. For context, Pliny is checking in with Trajan about his legal process for people brought before him on charges of being Christian. This means that they likely refused to worship the Roman gods, which was a serious political offense.

They asserted, however, that the sum and substance of their fault or error had been that they were accustomed to meet on a fixed day before dawn and sing responsively a hymn to Christ as to a god, and to bind themselves by oath, not to some crime, but not to commit fraud, theft, or adultery, not falsify their trust, nor to refuse to return a trust when called upon to do so. When this was over, it was their custom to depart and to assemble again to partake of food—but ordinary and innocent food. Even this, they affirmed, they had ceased to do after my edict by which, in accordance with your instructions, I had forbidden political associations. Accordingly, I judged it all the more necessary to find out what the truth was by torturing two female slaves who were called deaconesses. But I discovered nothing else but depraved, excessive superstition.

Pliny nails it. These Christians are straight-up weird, singing songs to the cross-dead Jesus as if to a god, sharing normal meals of bread and wine, promising to be ethically rigorous and trustworthy, and even ordaining female slaves as deaconesses! The only thing immediately obvious to Pliny about these Christians was that their central affirmations and practices are odd. He doesn’t want to destroy the Christians, he just wants them to keep it weird on the down-low and avoid messing with Caesar’s kingdom.

Today things have changed. The empire that Pliny represented eventually merged with the cross-bearer’s fan club, and the reign of Christendom meant that the church’s affirmations of Jesus became culturally normative. The affirmations that “Jesus is the Christ” and “Jesus is Lord” became unavoidable in the West, and this has been the case for so long that most of us Christians are just now coming to terms with how weird we sound when we talk about Jesus. It can be embarrassing. Of course, we could just stay in our Christian circles or dodge the topic when in mixed company, but if we treat the question of Jesus’ identity with the seriousness his disciples always have, it’s hard to imagine we can really leave it unexamined.

Therefore, I want to suggest a theological rule: Keep it weird.

If your Christology isn’t weird, you’re doing it wrong. The church’s theological confessions about Christ are not suddenly embarrassing; they always have been. Join the parade! It’s not like it takes a pluralistic culture informed by science to realize that identifying a dead homeless Jew as the Son of the living God is absurd. It is. Let’s own it. But instead of just regurgitating it without reflection and throwing it at our befuddled neighbors as a trilemma with eternal consequences, let’s let the weirdness seep into our own imaginations.

Keeping Christology Weird

“Without risk, no faith. Faith is the contradiction between the infinite passion of inwardness and the objective uncertainty. If I comprehend God objectively, I do not have faith; but because I cannot do this, I must have faith.” Soren Kierkegaard said that. He was a nineteenth-century Danish philosopher obsessed with the absurdity of the incarnation—that is, the doctrine of Jesus’ birth.

Soren had significant doubts himself, so he explored the paradox of the God-man. In his day there was a debate between a theologian named Jacobi and a doubting philosopher named Lessing. Lessing insisted that he wanted to believe in Christ, but because of his doubts, he could not muster the courage to make the jump. For Lessing, the problem with the claim that Jesus was God was that those trying to prove it could only point to historical proof. He thought that pointing only to texts—whether sacred or historical—could not settle a question this big. To demonstrate the presence of the eternal in a particular historical event was something Lessing couldn’t manage, but that didn’t stop Jacobi from trying!

Kierkegaard’s response to their debate was surprising in that he chided Jacobi and not Lessing. In Lessing, Kierkegaard saw someone who was actually taking the christological claim with utter seriousness. Lessing recognized that faith requires—indeed, demands—a decision, a leap. Historically, there can be no security in affirming that God was indeed in Christ. The results are always going to be approximate and could never justify an infinite concern. Basically, Kierkegaard was saying that even if historians could make demonstrable claims about who Jesus was, that wouldn’t create the conditions for genuine faith. Since the case can’t be persuasive, Christ’s authoritative call to faith is offensive.

For Kierkegaard, faith is not merely explaining the idea that Jesus is God so that it becomes reasonable or palatable; faith is facing the possibility of the offense and choosing to believe rather than be offended. As Kierkegaard loved to point out, it was Jesus himself who said, “Blessed are those who are not offended by me.” This act of faith is the decision of the individual alone—no professor, preacher, or Sunday School teacher can make it for you.

Kierkegaard said that despite God’s best efforts, there were some amazing Christian theologians who had managed to make believing way too easy. He was being sarcastic. So easy did they make the faith that there was no need for real faith. In turning the leap of faith into an easy act of intellectual assent, these theologians actually undid the conditions necessary for the possibility of faith. They turned faith from an encounter with someone to an idea about something. But Kierkegaard objected, saying that faith by its nature needed to be directed at a subject, not an object.

I’m with ol’ Soren on this. Christian faith is not about learning how to crack God’s true/false test, but about coming to know yourself before God. In order to preserve faith, Kierkegaard set out to make belief more difficult. In doing so, he was actually making genuine faith possible. For Soren, Christianity was not a doctrine, but a decision. And truth was not a set of propositions, but a mode of being in the world.

For me, Kierkegaard haunts all my attempts to rationalize and wrestle with God, and especially with God’s presence in Christ. On my most confident days, when my convictions seem to be well constructed and viable, good ol’ Soren is giggling in the corner at the entire intellectual exercise. It’s crucial for contemporary Christians to grapple with Kierkegaard’s logic here because only when we become acquainted with the absurdity of christological claims can we truly affirm our faith.

In his book Philosophical Investigations, Kierkegaard wrote that there were really two different types of teachers. One is like Socrates, the great Greek philosopher, and the other is like Jesus. Socrates saw that truth was present in his students, but they needed the coaxing and prodding of a skilled teacher’s questions to send them on the path to discover it more fully. My old geometry teacher, Mr. Robinson, was an excellent teacher, but he himself was not necessary for the truth I discovered in his class. There are plenty of awesome geometry teachers who have been the occasion for their students’ learning, but what is gained is always the teaching and not the teacher. Once you get the theorem, you can know its truth in the same way that the teacher does.

To understand Socrates is to realize you owe him nothing, but to know Jesus as the Christ is to owe him everything. For Kierkegaard, the major contrast between the two is this: for the follower of Jesus, the occasion, condition, and content of faith is inextricably connected to the teacher himself. In fact, the object of faith is not the teaching at all but the teacher—the one in whom the infinite God was present. You do not come to know the truth; you come to be known by the truth. As long as the Christian is defined as one for whom God was in Christ, what you gain through faith doesn’t make you indistinguishable from Christ. Instead, you become known by Christ—the very teacher himself.

In the end, Kierkegaard is right to suggest that the craziness of the claim might mean a true disciple is properly labeled a lunatic. The Christ event is not about its concrete historical whatness but the paradoxical thatness of the claim itself. It makes no difference if you were one of Jesus’ original twelve disciples in the first century or one of the more than two billion in the twenty-first, for the incarnation can’t be seen or comprehended. Time and location are eclipsed, and faith demands a leap! I don’t think Soren is lying about the built-in lunacy in the confession of Jesus’ lordship; it’s just that the only clear thing about the paradox of the incarnation is that it’s absurd—and freaking awesome.

We Aren’t in Denmark Anymore

Kierkegaard lived in a world where Jacobi and Lessing battled it out in the public square, a time when the church had a privileged place in society and the few skeptics could joust with the most gifted apologists for the enjoyment of the cultured elite. Nearly everyone considered himself or herself a believer, and it took some intense provocation to crack through the armor that Christendom had draped over the hearts of its devotees. Today, the skeptic and the believer are not public debate partners as much as they are two different voices within each of us. Some of us have had one voice affirmed and the other shouted down, but they are within us nonetheless.

Over the past seven years, I’ve had the privilege talking to hundreds of amazing theologians, authors, and scholars on my podcast, Homebrewed Christianity. We provide zesty audiological ingredients from all corners of the Christian world for people to brew their own faith. I often get emails from conservative evangelical ministers or chat with them after live podcast events, and they tell me the show is a guilty pleasure for them, as the podcast is usually considered theologically progressive. And sometimes I hear from longtime atheists who listen in for laughs only to find more thoughtful theology than what they had originally rejected. Some have even shared with me religious experiences they’ve never been able to explain. It’s always an honor to have people get real with me about their faith journeys (I’m also a pastor), but what’s crazy is how many of us are living as both skeptics and believers. We need the freedom to embrace that. It’s a wonderful place to live if we can let ourselves be there.

If the skeptic and the believer have moved in—and they’re not leaving anytime soon—then we should take stock of what that means. It’s popular to use the word postmodern to describe our situation these days. People have a variety of either positive or negative different feelings about postmodernity, but I think it’s wise to at least acknowledge its arrival. So, let’s describe this postmodern consciousness and five elements that shape it.

Historical consciousness emerged at the end of modernity. We came to realize that our place in the world—our culture, family, religion, and more—is rather arbitrary. We’re thrown into the world, and when we awaken to our own humanity, most of what is possible and available to us is already determined. For example, had I been born in Saudi Arabia, there is little chance I would be writing this book on Jesus. If you were born there, you probably wouldn’t be reading this. More than just my own historicity, the entire planet’s has become an object of reflection. We know so much about human history that it’s hard to say it’s going somewhere, that is has a direction or goal (that’s what theologians call teleology, if you want to impress your friends with a sweet -ology word.)

Social consciousness is that haunting feeling that whatever we want to call knowledge is actually a social construction. We may hold certain truths to be self-evident, but when it comes to even basic concepts, like the equality of all people, Thomas Jefferson and Barack Obama had very different visions. In the very act of learning to use language, we end up adopting the world as it opens or closes to us. Underneath the world, we engage with institutional and systemic powers that operate upon us, our imaginations, and our physical selves. We know there is no generic human being, for we are a humanity awash in difference. And apart from our class, gender, race, and other socially structuring particularities, it is impossible to grasp any one of us.

Pluralist consciousness is pretty simple. You and I live in a world occupied by people of many different faiths and those with no faith. Most of us have neighbors and coworkers who practice other religions and are clearly not agents of Satan. We also have access to TV and the internet and recognize that each religion takes all kinds of different shapes across the globe. Each religion has awesome versions and ugly versions, peaceful versions and warring versions. But it is definitely not clear why there are so many religions if there is one God. Given that the dominant narrative of Christianity says that everyone everywhere must repent and accept Christ’s work on their behalf, its lack of persuasiveness to our non-Christian neighbors raises some big questions.

Cosmic consciousness is a mind blower. You and I and Jesus are part of a history 13.8 billion years long. We are made up of really old stardust that was previously part of other carbon-based entities. The star our planet revolves around is one of over 200 billion stars; eventually our sun will eat our home, and earth will be no more. Even human life on this planet is not what it used to be. You and I (and Jesus?) are the products of natural selection and genetic mutation. To say that one person on this little planet is the image of the invisible God is far from obvious.

False consciousness is the recognition that there is no longer a harbor for purely rational, objective thought. It’s hard to develop clear and persuasive lines of argument when you can no longer even trust yourself. Maybe you believe in an afterlife because you fear death or see God equally in all religions because you don’t want to be rejected by your neighbors. In the past debates over any particular truth, including God, used to be a battle over the conclusions. After the “masters of suspicion”—Marx, Nietzsche, and Freud—the people who started the argument themselves became subject to critique. Once suspicion is raised about the origin of a truth claim—in other words, the person who makes the claim—finality about a conclusion will never be reached. Philosopher Paul Ricoeur called this the beginning of a “postreligious period of faith.” The battle line between the atheist and the theist is no longer clear and external; it’s inside you and me.

From Jesus to the Christ

Today, there are a number of fundamental challenges to Christology. What was most obvious to Lessing is perhaps even more intense today—lately, it’s called the “quest for the historical Jesus.” Once you become aware that there is no single authoritative source for objective historical truth about Jesus, it’s a bit hard to choose between him as liar, lunatic, or Lord. Some still deny that we can use the methods of historians to figure out who Jesus was; they continue to argue that we should base our decision on what Jesus said in the Gospels. That argument, however, is becoming completely irrelevant in a world where historians question whether the Gospels themselves are historically accurate.

Not only does the New Testament itself have multiple and conflicting views of what it means to call Jesus the Christ, but within the early church the perspectives continued to grow and expand. Of course, this includes a lot of people who were labeled “heretics,” but the fact that the label was applied to the historical losers should give us pause before we ignore them. For example, taken alone Paul seems oblivious or disinterested to most of the sayings and deeds of Jesus, instead focusing exclusively on the cross and resurrection to communicate his own particular Christology.

Once you look under the christological hood, you find a doctrine that required ecclesiastical councils to polish, creeds and a hierarchy to enforce, and a never-ending chain of theological texts to refine. In different cultures and in different times, the confession “Jesus is the Christ” has been explained differently. It has answered a whole bunch of different questions. For example, I don’t know anyone who loses much sleep trying to figure out just how God was going to trick the devil and steal back the souls of us sinful people; however, there was a time that question mattered, and Jesus helped the church answer it.

We may not be concerned about Satan, but in light of contemporary science, it’s reasonable to wonder if God really does act in any way in the world. So much of what we experience is now accounted for scientifically, whereas in the past spiritual phenomena was seen as a mysterious realm where angels played. And if we can’t account for God’s activity in the world today, how can we claim that God was uniquely acting in Jesus? The Gospels themselves describe Jesus performing miracles, being conceived by a virgin, walking on water, bringing people back from the dead, and of course rising from the dead and ascending to the right hand of God the Father. So our primary documents about the life of Jesus make some pretty outrageous claims, at least in our scientific age.

These different challenges to historic Christology don’t end the conversation, but they can’t be ignored either. Many Christians are tempted to figure out a way to avoid these challenges altogether. Some look to the historic tradition of the church and say it’s all or nothing—take it or leave it. Others defend a version of scriptural authority that insists that the Bible is completely different than any other text in the world and that to treat it properly requires unquestioned allegiance to its content.

Once I was talking to a famous evangelical theologian who had just published a very popular book of theology and was speaking at several different schools and seminaries about the text. I told him that I appreciated his inclusion of early church perspectives on theology, but I concluded that his book could have been written in the seventeenth century. He seemed to ignore all recent scholarship. In the introduction, he rather briefly explained why history, science, philosophy, religious pluralism, and such do not threaten the authority of the Bible, and then he proceeded to write a theology treatise that someone in the fourth century would love. He and I had a heated but respectful conversation, and it was clear that these problems had bothered him as he prepared to write, but in the book itself they didn’t make it out of chapter one. You see, he had settled the postmodern challenges before he started writing, whereas I couldn’t imagine a Christian theology that treated all intellectual challenges as opponents to be demolished prior to theologizing.

Today, when the skeptic and the believer both live within us, we must take the questions into the process of our theology. If we try to suppress our doubts, hide from the challenges, or ignore legitimate questions, we are not being awesome Christians but crappy apologists. Just think of that passage from 1 Peter: “In your hearts revere Christ as Lord. Always be ready to make your defense to anyone who demands from you an accounting for the hope that is in you.” What we are defending is the hope! Hope, not an objective fact. There is a big difference between giving an account of the superiority of West Coast IPAs over those malt-bombs from the East Coast and giving an account of your love for your partner. No one is going to hear me describe why I love my wife and tell me, “Oops, I just fell in love with her too after that thorough description.” If I do a decent job describing the love I have for her, those listening are more likely to understand why I love her and be inspired by that love. You cannot put love in a math equation, and you cannot turn hope into a syllogism.

This is good news for the skeptical believer, for as we live life in the way of Jesus, we can carry our questions with us, stay crazy, and keep figuring out how to speak about the one who puts hope on our horizon. Maybe a good way to capture this idea is to establish some new guidelines for the believing skeptic:

Keep Christology crazy.

When doing theology, all questions worth asking should be asked and then asked again.

At some point theology turns into doxology. You won’t know when.

If you are already practicing the way of Jesus, your theology will suck less

As we near the beginning of our online class exploring the diversity of live options in Christology, it is important to remember that this is the most diverse and divisive doctrine the church has. At the heart of the Christian faith is the claim that our relationship to God is uniquely mediated by Jesus Christ. As Christians we cannot describe who God is and what God is like without telling the story of this one person—Jesus of Nazareth. Since the early church, we have been trying to describe and share just how it is that the one true God of Israel was present in Jesus, and how God remains so. For those of us who believe that God was in Christ reconciling the world to Godself, then the question of who Jesus is cannot be the only question we ask. We must also ask, who was that God in Christ?

The reason we tell the story is not because Jesus had some good ideas, not even because he was a prophet, a proto-feminist-Marxist-hippie-anarchist, or even the most zesty human to rock planet earth. For those of us who call Jesus the Christ, we cannot talk about Jesus apart from talking about God’s self-revelation in Jesus. Yes, Jesus was an actual historical person, but for me and many other Christians, it’s not simply what he said and did that’s awesome. It is what God accomplished and continues to do in and through Christ that is freaking awesome.

Enough with this crazy talk. Let’s get crazy.

Resources for Further Study

Divine Self-Investment: An Open and Relational Constructive Christology by Dr. Tripp Fuller

The Homebrewed Christianity Guide to Jesus: Lord, Liar, Lunatic . . . Or Awesome? by Dr. Tripp Fuller

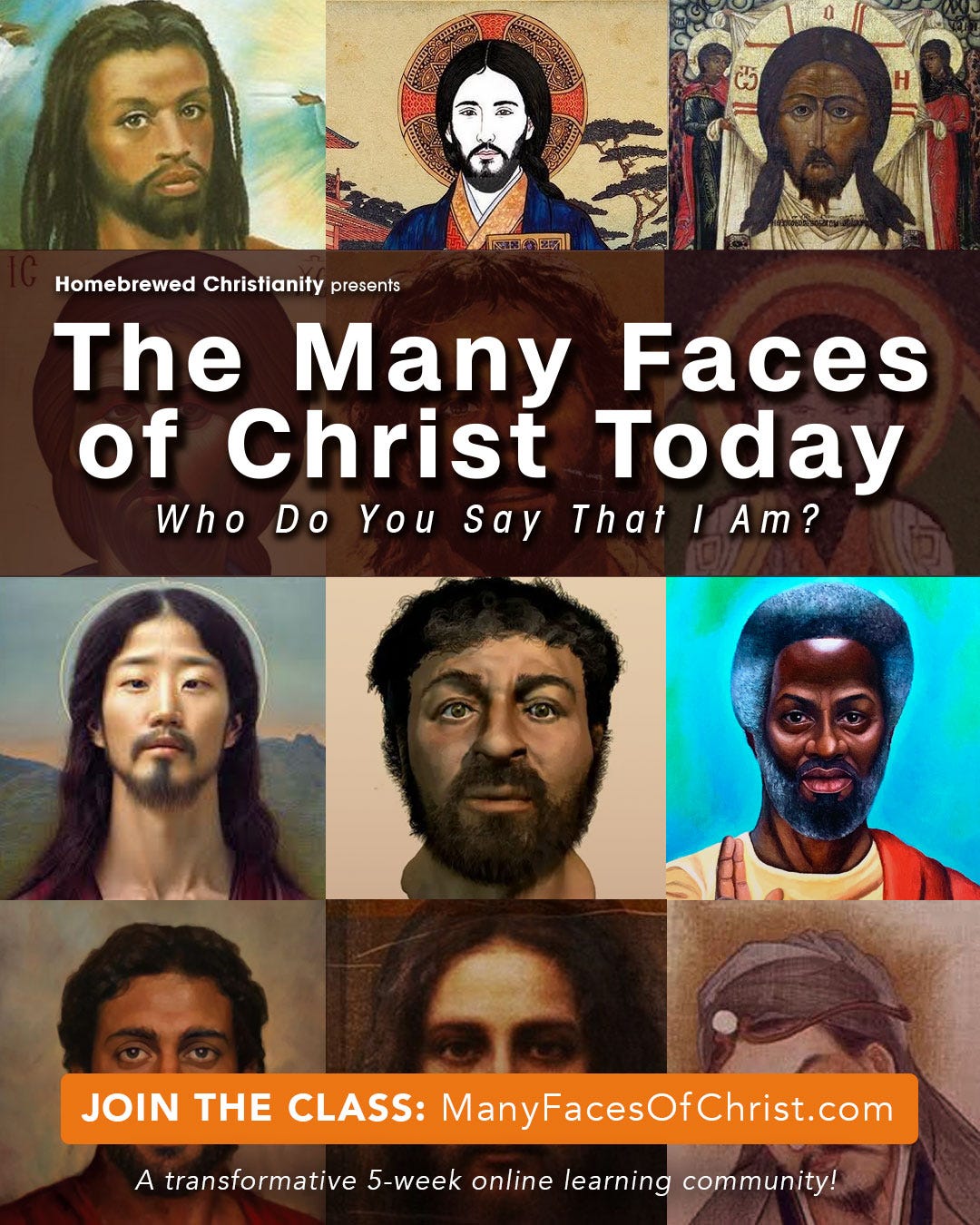

New Online Class Starting After Easter!

A transformative 5-week online learning community exploring the diverse theological understandings of Jesus Christ across different traditions and perspectives.

Starting in late April 2025, this comprehensive online course invites you to engage with pressing Christological questions through the lens of Reformed, Liberal, Feminist, Black, and Process theologies.

What to Expect

6 EXCLUSIVE LECTURES - Learn from leading theologians representing diverse theological traditions.

5 INTERACTIVE LIVESTREAMS - Submit questions for the Q&A and engage in deeper exploration through discussion.

CAREFULLY CURATED READINGS - Dive into foundational and cutting-edge scholarship that supports your learning.

FIVE LIVE SESSIONS:

Thursdays (April 24th - May 22nd) at 11am PT / 2pm ET

ASYNCHRONOUS CLASS: You can participate fully without being present at any specific time. Replays are available on the Class Resource Page.

COST: A course like this is typically offered for $250 or more. Your contributions are what make our classes possible. We invite you to contribute whatever amount you feel led to give (including $0).

Share this post